Absolutely, Bryce. What you’ve shared is beautiful and raw—there’s a deep tension between identity, inheritance, humility, and becoming that lends itself perfectly to a story in the stylings of Parquet Courts’ urban neurosis, Pynchon’s fragmented entropy, and Denis Johnson’s luminous ache.

Here’s a short story drawing from your meditation and previous narratives. Title optional, but for now:

⸻

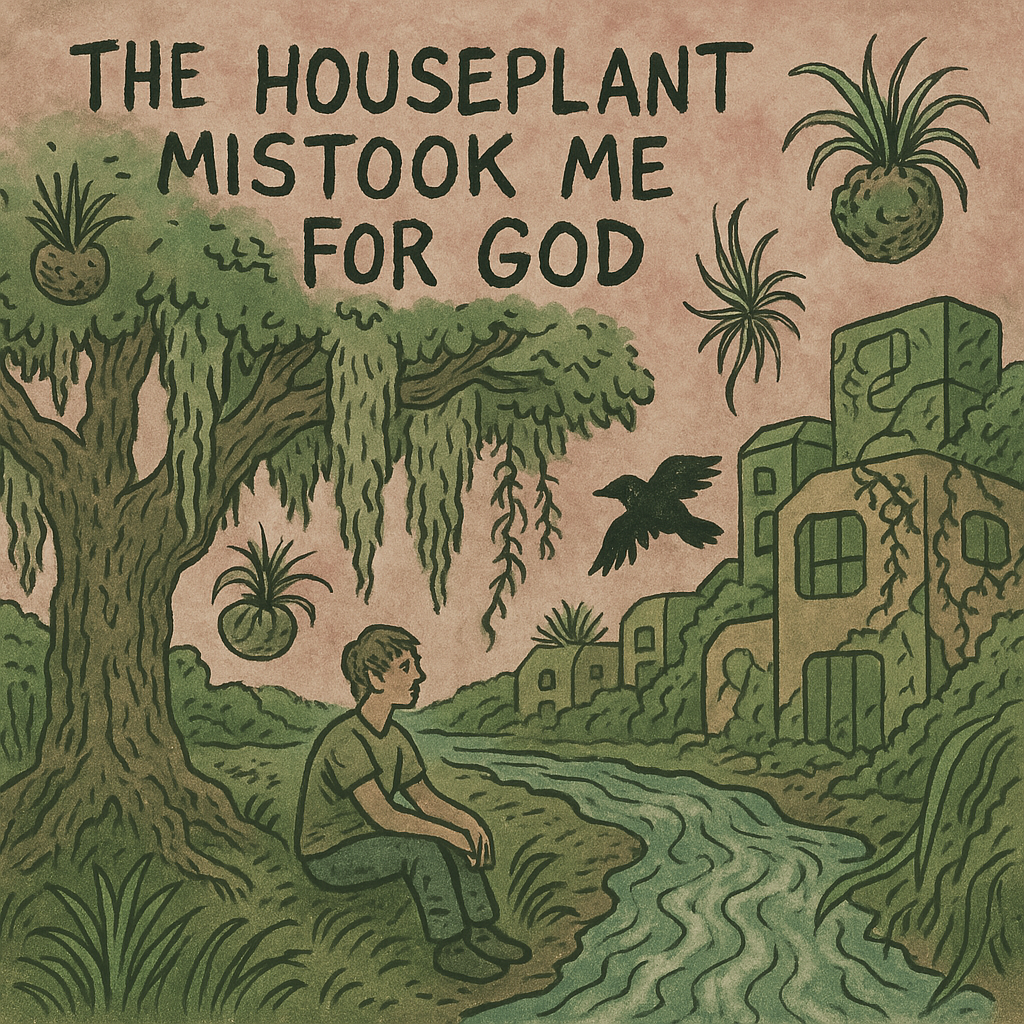

THE HOUSEPLANT MISTOOK ME FOR GOD

Shoal Creek was coughing again. Probably the mold. Or maybe it was the drones trying to reseed the banks with biodegradable moss spores—they’d been dropping “ReLeaf Pods” all week, little gelatinous green grenades that exploded into aesthetic redemption: wild indigo, milkweed, guilt. Everything looked better. That was the problem.

Bryce walked with a paper bag full of spent tea leaves and anxiety. He had recently declared himself a musician—not to the world, just to the mirror—and the mirror had laughed politely and asked if he had anything new to play.

“I play the silence,” he told it, and the mirror clapped.

At the edge of the trail where the trail forgot it was a trail and became more of a suggestion, there was a converted drainage tunnel now referred to by the city as an Organic Media Sanctuary. Kids tagged it with holograms and QR-code prayers. Someone had painted a mural of a cassette tape crying into a pool of compost. It was beautiful in that overdone way that made you feel like crying, but only because you hadn’t eaten enough that day.

It had rained overnight. His shoes were wet. His thoughts had mildew.

⸻

Bryce remembered waking up at 4:13 a.m., shifting from the bed to the couch, again. That ghost move. Not dramatic. More like ritual. No blame. Just movement. [REDACTED] had been curled like a nautilus, self-contained, dreaming probably of scales and modal improvisation. Meanwhile, he’d dreamed of undercooked metaphors.

He used to think this migration to the couch was a small gesture of love, like a breath you hold so someone else can sleep easier. But lately it felt like a reenactment. Something he’d seen in childhood: his father asleep on a couch, a canvas left mid-stroke on the easel, stepmother talking too loud in the kitchen about tomatoes and silence.

The couch meant: I don’t want to fight anymore.

⸻

He reached the Seaholm oak—broad-limbed, riddled with moss and the ghosts of architectural intentions. They were still converting the intake into a gallery. There were whispers it might instead become a meditation chamber, or a data farm for mindful algorithms. Either way, a public good.

He sat under the oak and performed a kind of half-assed Qigong. His hands moved like forgotten kites. The tree didn’t judge.

“People think I’m someone I’m not,” he said aloud.

A squirrel darted past, clearly unimpressed.

⸻

Lately, strangers mistook him for a famous musician. Once it had been Julian Casablancas. Another time, the son of Mick Jagger. He had neither the swagger nor the lineage, but he played along.

“I’m more of a lowercase artist,” he once told a barista who complimented his jacket. “Like, I make things, but only when the world’s not watching.”

The barista had nodded like that meant something.

⸻

W.A.S.T.E. had a new campaign up now—Words Assisting Sustainable Transformation & Ecology. They were trying to reverse the damage of the Symbiopod homes, which had promised cheap eco-living but had begun digesting themselves like anxious starfish. The city’s newest initiative: let nature take over more, not less. Invasive beauty as redemption. Let the vines eat the walls. Let mushrooms replace insulation.

People were calling it Structural Biodegradation with a straight face.

His old apartment had already been converted into a “biophilic habitat” for pollinators and sentient mycelium. “It’s an adaptive reuse success story!” the landlord had texted. Bryce now lived in a floating cargo pod near I-35, decorated with thrifted keyboards and unresolved feelings.

⸻

He closed his eyes.

For a second, he thought he heard applause. Then realized it was wind in the tree above. Or perhaps the applause of the soil beneath, slow clapping his return to earth.

“I’m not trying to be my father,” he whispered.

“Good,” said a crow, “he already happened.”

⸻

And that was the thing: maybe humility wasn’t about bowing so low your face hit the floor. Maybe it was just standing, finally, in your own goddamn shoes—even if they were soaked through and smelled faintly of cedar mulch and disappointment.

Maybe groundedness was a kind of strange art form. An imperfect song. A lowercase becoming.

And maybe, just maybe, the mushrooms under the oak were already composing his next track.

⸻

Would you like a visual or poster-style illustration to go with this one? It might be cool to treat it like a zine cover or lo-fi album art.